The first time I understood, and I mean understood in my bones, that something was wrong, I was less than five minutes in to a run.

It was a warm summer day in Altoona, Pennsylvania, and I took off from my house, intent on running what was then a familiar seven-mile route to the Horseshoe Curve.

Runners will tell you that a run often feels hardest in the first 15 minutes.

My body felt different right from the start this time. My legs felt as though someone had filled them with rocks. My shoulders felt like I was wearing every piece of winter clothing I had. My feet seemed to be moving through mud.

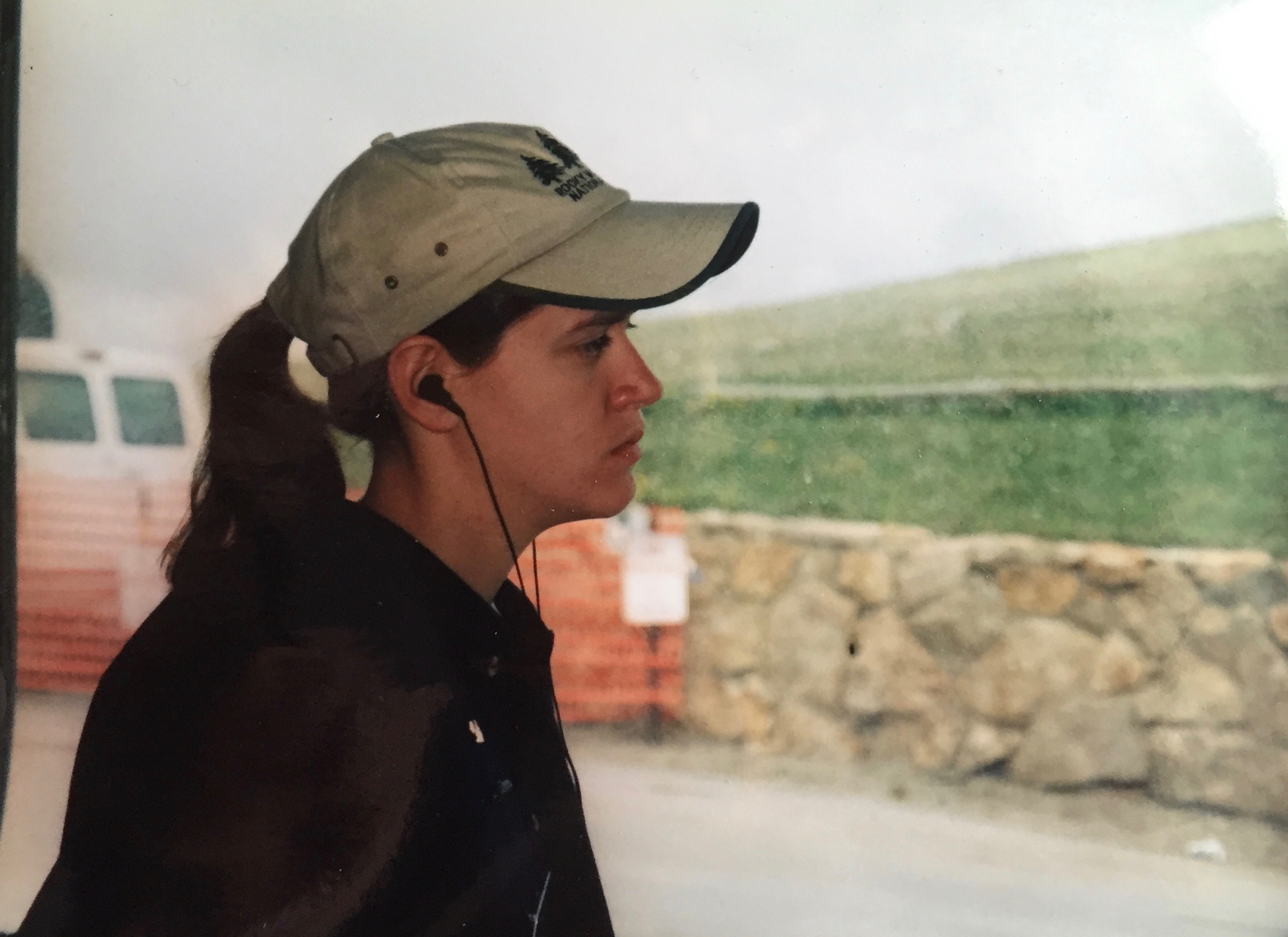

A friend snapped this picture when I was working at Trail Ridge Store in Rocky Mountain National Park and I had no idea. I was surrounded by the beauty of the park, but often couldn't take it in.

Runs are often hard. But this day was different.

Less than a half-mile later I finally stopped. Standing along the side of the road, hands on my knees, staring at gravel and asphalt, I found myself somewhere between apathy, fatigue, and a growing anxiety.

I turned and walked back to the house. I crawled onto the couch and spent the rest of the day there, battling a tidal wave of feelings:

Fear. I didn’t understand what was happening, but physically, I felt off.

Guilt. I’d set out to run seven miles and didn’t.

Shame. I was soaked in the shame and failure of my poor excuse for a life.

And hopelessness. I didn’t see how anything would get better.

I was 28 years old, working at a camera shop for minimum wage; trying to decide what to do with my life and feeling embarrassed that I hadn’t done more. By then I’d started and left two graduate programs in two different fields, feeling woefully inadequate as a student.

I’d stalled out in my effort as a writer, constantly battling to find motivation and focus.

For most of my twenties, running was the one thing that left me with a sense of accomplishment in my day-to-day life. No, I didn’t have a profession and I wasn’t the writer I’d hoped to be, but I could check off the runs and return to another sleepless night feeling as though I’d done something.

Without running I had precious little to hold onto. That failed run took away the last little bit of hope I had of amounting to anything in my life.

I’d like to say that I did something about my depression that same day. But I didn’t. A few days later, driving along a rural Pennsylvania road I was overcome with a desire to end it all. One quick turn of the steering wheel, a heavy foot on the gas pedal and a run in with a tree and it would all be over. And everyone else would be better off without me.

For a split second I looked down at the steering wheel and wasn’t sure what I was going to do. I slowed down, pulled over to the side of the road and sat in the car for a few minutes.

Then I finally decided to do something about it.

My battle with depression

If you met me today, I think (hope) there are two truths about me that you’d find surprising.

I’m an introvert. (Honestly. I hid behind my mother’s legs until I was taller than she was. It was awkward).

I’ve been treated for depression for the past 11 years.

I hope the second one is surprising because you experience me as happy. Maybe even fun. But I really hope you see my happiness, because I have worked harder at my happiness than I’ve worked at anything else in my life.

This is a recreation of the word art I did in sixth grade. It was both witty, sad, and a cry for help.

In retrospect, I was depressed for most of my life. In sixth grade we had to make word art - choose a word and animate it. I chose the word depressed. I tried to make it funny, with two big D’s on the end and the rest of the word smaller. But the addition of crying eyes in the capital D’s should have let someone know I was struggling.

High school and college helped mask some of my struggles. I always had sports to keep me focused. I did well enough in school, I worked on the college and high school newspapers.

Late in my senior year of college, I began a downhill slide that would last for well over a year. It began with the personal discovery that I was gay, which happened when I was 21. And that discovery left me feeling so rejected by God and religion and society that I was sure suicide was my only option. I was a devout Catholic; being gay was not an option and pretending I was straight involved a lie I couldn’t live.

But thankfully, I had enough hope to plod on. And I thought that my ability to plod on meant that I wasn’t depressed. I knew from other people and the media what depression could look like. And I didn’t think it looked like me.

My mistake through all of these periods of time was thinking that my experience was all there was to life. I had highs and lows, but the lows were really low and the highs were never very high.

Not long after my failed run, I was diagnosed with dysthymia, also called persistent depressive disorder. The description from the Mayo Clinic is “a continuous long-term (chronic) form of depression. You may lose interest in normal daily activities, feel hopeless, lack productivity, and have low self-esteem and an overall feeling of inadequacy. These feelings last for years and may significantly interfere with your relationships, school, work and daily activities.”

The above paragraph described my life, but it had been that way for so long, I thought it was normal. It was my normal.

It wasn’t until that day, that failed run, that I finally had to acknowledge that while I was functioning and showing up for life, I was hanging by a thread. Yes, I was functioning. But just barely.

I only lasted for six months at the University of New Mexico before a second major depressive episode sent me back to Pennsylvania.

And for the first time I admitted that it wasn’t just a question of pulling myself up by my bootstraps. I needed help doing that.

Seeking help

I’d had a therapist for a little while in my twenties, but I’d been denying that anything was really wrong. I was in therapy to help unclog my creativity, but I was certain that depression wasn’t a part of it.

Once I scared myself with the impulse to wrap my car around a tree, I was finally a little more honest. And as I mentioned in a previous post, I came face to face with the real answer to the question, “how’s that working for you?”

The big hurdle for me was to try anti-depressants. They are not for everyone. They do not fix everything. And it takes awhile to find the right one. In my case, it took over six months to even begin coming out of the fog. But once I did, I made the big changes that I hadn’t been able to make before.

I picked up my life and moved to Boston. I finally went back to graduate school and finished. I found the person with whom I’ll spend the rest of my life. And after years of struggle to focus and persist, I have not just a job, but a career.

I can say with confidence that these things would not have happened if I hadn’t treated my depression. And continue to treat it. Medication doesn’t eliminate the depressive episodes. A therapist doesn’t eliminate them either; but the combination of the right support network is crucial to surviving a disease that can be so debilitating.

If I had one message to share with anyone reading this, it’s that you’re not alone, even though it feels that way. It can feel as if no one understands. It can feel hopeless. According to the CDC, as many as 1 in 10 adults report symptoms of depression, and I imagine a number of you reading this have probably suffered from depression at some point in your lives.

And if you need a lifeline, there is one. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is a 24-hour resource; call, chat, or text at 1-800-273-TALK, and http://www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/. The Lifeline can also refer you to resources and counseling in your area.

There is help. There is hope. And there is a light that can shine through that darkness.